+86-15889090408

[email protected]

The Himalayan mountain ranges, often referred to as the “abode of snow,” stretch across five countries, with Tibet hosting some of its most awe-inspiring sections. This blog explores the Himalayas’ Tibetan segment, delving into its geological wonders, cultural richness, and breathtaking landscapes. Whether you’re an adventurer, a nature lover, or a cultural enthusiast, Tibet’s Himalayas offer a transformative experience.

The Himalayan mountain ranges, particularly those within Tibet, are not just a breathtaking natural wonder but also a geological masterpiece shaped over millions of years. Understanding their formation and significance requires delving into the dynamic forces of tectonic collisions, the unique characteristics of the Tibetan Plateau, and the profound impact these mountains have on global climate, ecology, and human civilization.

The story of the Himalayas begins roughly 50 million years ago during the Eocene epoch, when the Indian Plate, drifting northward at a rate of 15 cm per year, collided with the Eurasian Plate. This monumental collision, one of the most dramatic tectonic events in Earth’s history, marked the start of the Alpine-Himalayan Orogeny—a mountain-building process that continues to this day.

As the dense Indian Plate slid beneath the Eurasian Plate in a process called subduction, the crust crumpled and folded, thrusting upward to form the Himalayan range. The collision compressed sedimentary layers of the ancient Tethys Ocean, creating metamorphic rocks like schist and gneiss, as well as marine fossils now found at towering altitudes.

The Indian Plate continues to push northward at 5 cm per year, causing the Himalayas to rise approximately 1 cm annually. This relentless movement generates frequent earthquakes, such as the devastating 2015 Nepal earthquake, and keeps the region geologically volatile.

The Himalayas in Tibet are inseparable from the Tibetan Plateau, often dubbed the “Roof of the World” for its average elevation of 4,500 meters (14,764 feet). This plateau is the largest and highest on Earth, covering 2.5 million square kilometers—an area larger than Western Europe.

The plateau’s elevation is a direct result of the Indian-Eurasian collision. As the Indian Plate subducted, it not only pushed up the Himalayas but also thickened the crust beneath Tibet, creating a vast, elevated plain. Geologists refer to this process as crustal shortening, where the crust folds and stacks like a rug being pushed against a wall.

Thickened Crust: The Tibetan crust is up to 70–80 km thick (double the global average), creating a gravitational anomaly that influences regional geology.

Mantle Dynamics: The plateau’s uplift is also driven by the delamination(peeling away) of the lower crust and mantle lithosphere, allowing hotter asthenosphere to rise and further elevate the land.

Extensional Faults: Despite compression, the plateau is stretching east-west due to gravitational collapse, forming rift valleys like the Yadong-Gulu Rift.

The Tibetan Himalayas and plateau play a critical role in regulating global and regional climate systems, earning them the nickname “Asia’s Water Tower.”

The plateau acts as a heat engine in summer. Its elevated surface absorbs solar radiation, heating the atmosphere and drawing moisture-laden winds from the Indian Ocean. This creates the South Asian monsoon, vital for agriculture in India, Nepal, and Bangladesh.

By blocking monsoon winds, the Himalayas create a stark climatic divide. The southern slopes receive heavy rainfall (e.g., Cherrapunji, one of the wettest places on Earth), while the Tibetan Plateau remains arid, with annual precipitation as low as 100 mm in some areas.

Tibet’s Himalayas feed 10 major river systems, including the Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra (Yarlung Tsangpo), Yangtze, and Mekong. These rivers sustain over 1.5 billion people downstream. However, climate change is accelerating glacial melt, threatening water security across Asia.

The geological forces that shaped Tibet’s mountains also endowed the region with extraordinary mineral and energy resources.

Metallic Ores

The collision zone is rich in copper, gold, lithium, and chromite. The Qulong Copper Deposit in southern Tibet is one of Asia’s largest, holding over 10 million tons of copper.

Geothermal Activity

Hot springs and geothermal fields, such as Yangbajing, harness the tectonic energy of the plateau. These sites are culturally significant to Tibetans and are increasingly tapped for clean energy.

Fossil Discoveries

The Himalayas preserve ancient marine fossils, including ammonites and trilobites, offering clues to the Tethys Ocean’s history. The Mount Everest region contains limestone layers with 400-million-year-old fossils, now perched at 8,000 meters.

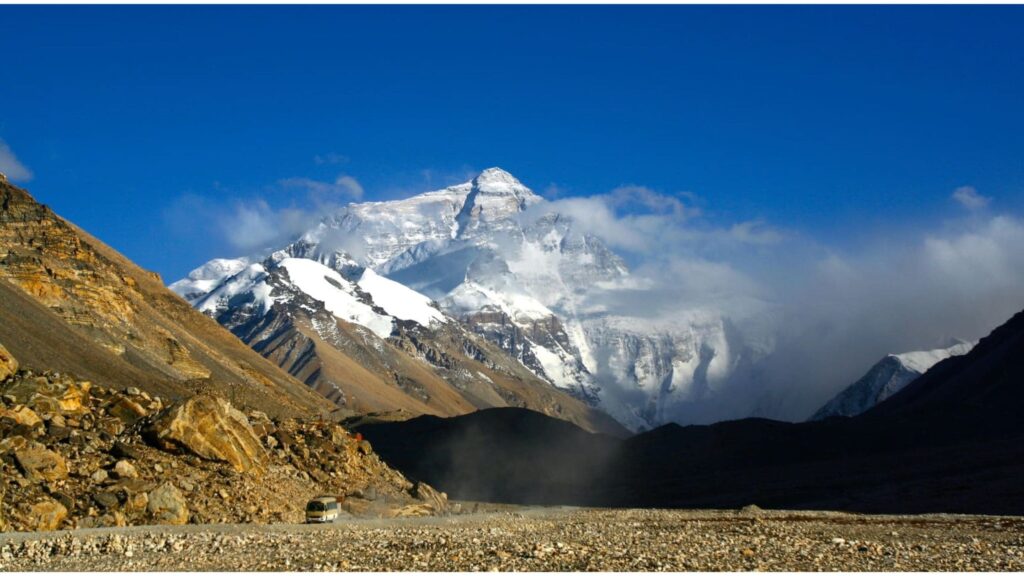

– Mount Everest (8,848m): The world’s highest peak, straddling Tibet and Nepal. The Tibetan side offers the North Face, a challenging climb with dramatic vistas.

– Shishapangma (8,027m): The only 8,000m peak entirely within Tibet, revered by locals.

– Makalu (8,485m) and Lhotse (8,516m): Neighboring giants visible from Everest, popular among seasoned climbers.

The plateau, spanning 2.5 million square kilometers, features:

High-Altitude Deserts: Sparse vegetation and surreal rock formations.

Pristine Lakes: Namtso and Yamdrok, sacred to Tibetans, reflect Himalayan peaks.

River Systems: The Brahmaputra (Yarlung Tsangpo) and Indus rivers originate here, sustaining millions.

Despite harsh conditions, Tibet’s Himalayas harbor unique ecosystems:

Flora: Alpine meadows bloom with poppies and edelweiss in summer.

Fauna: Snow leopards, Tibetan antelopes, and black-necked cranes thrive here. Conservation initiatives aim to protect these species from climate change and habitat loss.

Sacred Sites: Mount Kailash, a pilgrimage site for four religions, symbolizes spiritual enlightenment.

Monasteries: Rongbuk Monastery, the highest in the world, serves as a gateway to Everest.

Festivals: Losar (Tibetan New Year) showcases vibrant dances and rituals rooted in mountain worship.

Tourism and Trekking Opportunities

Everest Base Camp (Tibet Side): Offers panoramic views without the crowds of Nepal.

Kailash Mansarovar Pilgrimage: A spiritual trek circumambulating Mount Kailash.

Best Time to Visit: April–October for stable weather. Permits are required; plan with registered agencies.

Climate change and tourism pressure threaten Tibet’s fragile ecosystems. Organizations work to promote sustainable practices, such as waste management in trekking areas and anti-poaching patrols. Visitors can contribute by minimizing their environmental footprint.

The Himalayan mountain ranges in Tibet are a testament to nature’s grandeur and cultural resilience. From the summit of Everest to the tranquil shores of Namtso, Tibet’s landscapes inspire awe and reverence. By embracing responsible tourism, we can preserve this legacy for future generations. Explore Tibet’s Himalayas—where earth meets the sky, and adventure meets spirituality.