+86-15889090408

[email protected]

Tibetan Thangka paintings are not merely art; they are a profound reflection of the spirituality, history, and culture of Tibet. With their intricate details, symbolic meanings, and vibrant colors, Thangka paintings have long been central to Tibetan Buddhist practices, playing a vital role in meditation, religious rituals, and teaching. To understand the full impact of Thangka art, we need to delve into its history, significance, techniques, and role within Tibetan culture.

In this blog post, we will explore Tibetan Thangka paintings in depth—discussing their origins, significance in Tibetan Buddhist practice, key elements, techniques, and their place in Tibetan art history. This exploration will also reveal the unique role these paintings play in preserving Tibetan culture.

• Religious Imagery: Thangkas almost always portray religious icons or spiritual figures. They often include deities from the Tibetan Buddhist pantheon, such as Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, and Tara, as well as historical figures like the Dalai Lamas or famous saints.

• Mandala Designs: Mandalas are intricate geometric designs that symbolize the universe in Tibetan Buddhism. Many Thangkas feature mandalas at their center, representing the cosmos or a sacred space for meditation.

• Bright Colors: Thangkas are renowned for their vibrant colors, particularly the use of reds, yellows, greens, blues, and golds, which symbolize different aspects of Buddhist teachings.

• Symbolism: Every element in a Thangka is infused with symbolic meaning. From the positioning of figures to the colors and patterns, everything serves a higher spiritual purpose.

Tibetan Thangka painting is one of the most distinctive and revered forms of art in the world. Known for its intricate details, vibrant colors, and profound spiritual significance, Thangka art has been an integral part of Tibetan Buddhist culture for centuries. The history of Tibetan Thangka painting is not just a tale of artistic evolution, but a chronicle of religious devotion, cultural exchange, and spiritual enlightenment.

In this blog post, we will explore the origins, development, and evolution of Tibetan Thangka painting, delving into the key historical periods, influential figures, and cultural exchanges that have shaped this remarkable art form. Whether you are an art enthusiast, a historian, or someone simply curious about Tibetan culture, this journey into the past will give you a deeper understanding of the rich legacy of Tibetan Thangka art.

Before delving into the history, it is important to understand what a Thangka is. A Thangka (Tibetan: ཐང་ཀ་, pronounced “tang-ka”) is a traditional Tibetan scroll painting, typically depicting Buddhist deities, saints, and scenes of religious teachings. The paintings are usually made on cotton or silk canvas, and their detailed and symbolic imagery serves as both a work of art and a sacred object for meditation, teaching, and worship.

Thangkas can be rolled up and stored or carried easily, which makes them convenient for use by monks and pilgrims. They are often used in religious rituals, festivals, and ceremonies, and can be displayed on walls in temples, monasteries, or homes. The central figures in a Thangka often represent divine beings such as Buddha, Bodhisattvas, or tantric deities, while surrounding motifs might include mandalas, geometric patterns, and symbols of enlightenment.

The origins of Tibetan Thangka painting are closely tied to the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet, which began in the 7th century CE. Buddhism arrived in Tibet from India and Central Asia, primarily through the efforts of Indian missionaries, scholars, and the patronage of Tibetan kings.

The first major push to spread Buddhism in Tibet occurred during the reign of King Songtsen Gampo (r. 617–650). Songtsen Gampo, who was instrumental in the early stages of Tibetan Buddhism, married two Buddhist princesses, one from Nepal and one from China, and brought Buddhist scriptures, teachings, and artwork into the Tibetan court.

During this time, Indian Buddhist art began to influence Tibetan artistic traditions, including the creation of religious paintings. Early Tibetan art was heavily inspired by Indian artistic forms, which is evident in the early Thangka paintings that depicted Buddhist deities like their Indian counterparts. However, these early works were still relatively simplistic, and the development of a distinctly Tibetan style was still in its infancy.

In the 8th century, the reign of King Trisong Detsen (r. 755–797) marked a crucial turning point in the development of Tibetan Buddhism and the art associated with it. King Trisong Detsen invited the Indian Buddhist scholar Padmasambhava (also known as Guru Rinpoche) to Tibet, who is credited with establishing the first monastery, Samye, in 779 CE. This monastery became a center for both religious learning and artistic expression.

With the establishment of Samye, a formalized tradition of Thangka painting began to take shape. Monastic painters, often monks themselves, began to create images of Buddha and other deities, and the use of Thangkas as religious tools for meditation and teaching became more widespread. Thangkas were also used in ritual ceremonies to invoke the blessings of deities and to guide practitioners toward spiritual enlightenment.

The period between the 11th and 14th centuries is often considered the “Golden Age” of Tibetan art, and it was during this time that Thangka painting truly began to evolve into the distinct and highly refined style we associate with it today. This era saw the rise of various Tibetan Buddhist schools, each with its own interpretations of Buddhist teachings and artistic styles.

During this time, Thangka painters began to adhere to more standardized iconographic rules. Artists developed intricate, codified designs for different deities, mandalas, and Buddhist symbols. This period also saw the emergence of a specific Tibetan color palette, which included vibrant hues of red, yellow, blue, green, and gold, each color having symbolic significance in Buddhist thought. Gold, for example, was often used to highlight the most important figures or divine aspects, representing purity and spiritual illumination.

Throughout this period, Tibetan art continued to be influenced by the great Buddhist art traditions of India and Nepal. Many of the early Tibetan Thangkas were created by artists who had trained in India or Nepal, and the imagery often mirrored the artistic conventions of these regions. Indian Buddhist art, particularly from the Pala Dynasty (8th to 12th century), had a lasting influence on Tibetan artists, particularly in the portrayal of deities and figures. The elaborate iconography and devotional symbolism of the Indian tradition helped shape the structure and themes of Tibetan Thangka painting.

By the 12th and 13th centuries, Tibetan Buddhism began to spread beyond the borders of Tibet into the surrounding Himalayan regions, including Nepal, Bhutan, and Mongolia. As Buddhism spread, so too did the influence of Tibetan Thangka painting. The Tibetan monastic tradition became the main institution for the training of artists, and these artists began to travel throughout Asia, producing Thangkas for monasteries, temples, and courts.

One of the most important developments of this period was the increasing use of Thangkas in the process of Buddhist meditation and practice. Thangkas were not only beautiful works of art but also served as essential tools for meditation, helping practitioners visualize deities, cosmic diagrams, and sacred teachings. Thangkas became central to Vajrayana Buddhism, the “Diamond Path” of Tibetan Buddhism, where visualization of spiritual figures is an important aspect of spiritual training.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties (14th to 18th centuries), Tibetan Thangka painting continued to develop under the auspices of the growing Tibetan Buddhist monastic system. Tibetan Thangkas of this period became more refined, with highly detailed depictions of Tibetan Buddhist cosmology, historical figures, and the lives of the Buddha.

During this tumultuous period, many Tibetan monasteries were destroyed, and Buddhist practices, including Thangka painting, were severely suppressed. The destruction of Tibetan culture during the Cultural Revolution led to the near extinction of traditional Thangka painting in Tibet.

Today, Tibetan Thangka painting is experiencing a global revival. With growing interest in Tibetan culture and Buddhist practices around the world, Thangkas are being appreciated not only for their spiritual significance but also for their artistic mastery. Thangkas are sought after by collectors, galleries, and institutions worldwide, and many contemporary Tibetan artists continue to follow the traditional methods of Thangka creation.

Tibetan art schools and workshops in India and Nepal have produced many skilled artists who continue the traditions of Thangka painting, while also experimenting with new materials and themes. Thangkas are now displayed in museums and galleries worldwide, showcasing the beauty and spirituality of this unique form of art.

The history of Tibetan Thangka painting is a testament to the resilience and continuity of Tibetan culture and spirituality. From its humble beginnings in the 7th century to its current global recognition, Thangka painting has played a central role in the religious and cultural life of Tibet. Each painting, with its intricate details and profound symbolism, tells a story of devotion, enlightenment, and the enduring spirit of the Tibetan people.

Whether as sacred objects for meditation or as works of art to be admired, Thangkas will continue to serve as a bridge between the material world and the divine, preserving Tibetan Buddhist teachings for generations to come.

Buddhism arrived in Tibet during the reign of King Songtsen Gampo (7th century), who played a key role in introducing Buddhist teachings and culture to the Tibetan people. At this time, Buddhism came to Tibet from India via Nepal and China. Initially, Thangka paintings were influenced by Indian Buddhist art and iconography, which is why we see similarities in the representation of deities, color schemes, and symbolic motifs between Indian and Tibetan Buddhist art.

During the reign of King Trisong Detsen (8th century), the first monastery, Samye, was built in Tibet, and more elaborate religious practices began to take hold. Monks were trained in Buddhist scriptures, and artistic traditions began to flourish. Thangkas were created as a way to visualize complex Buddhist teachings, providing a medium for meditation and a tool for the propagation of Buddhist philosophy.

The golden age of Tibetan art began in the 11th century, after the revival of Buddhism in Tibet and the establishment of various schools of Tibetan Buddhist thought. Tibetan art began to gain distinctive characteristics, diverging from Indian influences and developing unique features, such as the use of more refined lines, elaborate decorative borders, and the distinctive Tibetan color palette.

During this period, the first great masters of Thangka painting emerged. These artists were highly revered, often trained in monastic schools, and worked under the auspices of religious institutions. Their creations were not only religious artifacts but also instruments for spiritual practice, allowing for meditation on the divine through visual means.

Thangkas hold an essential place in the religious practices of Tibet. They are not just paintings; they are sacred objects. In Tibetan Buddhist practice, Thangkas are used as teaching tools, guides for meditation, and instruments for initiating rituals.

1. Visualization of Deities: Thangkas allow monks and practitioners to visualize deities during meditation. The images serve as a focal point for concentration, guiding the practitioner towards a deeper connection with the divine.

2. Aids to Meditation: Thangka paintings are often used as a visual aid in meditation practices, particularly in the Vajrayana Buddhist tradition. The intricate details, colors, and symbolic meanings help practitioners deepen their spiritual practice.

3. Educational Role: Thangkas also play an important role in teaching the principles of Buddhism. They often contain intricate details about Buddhist cosmology, teachings on the path to enlightenment, and stories from the lives of great Buddhist saints. These visual depictions allow even illiterate people to understand complex religious teachings.

4. Rituals and Offerings: Thangkas are often used in religious ceremonies, such as pujas (ritual offerings) and teachings. Monks might offer incense or perform rituals in front of the Thangka, using it as a medium to communicate with the divine.

Creating a Thangka is a meticulous and highly specialized art form, requiring years of training and discipline. The process is often carried out by skilled monks or artists who have mastered the techniques handed down through generations.

• Canvas: Thangkas are typically painted on cotton or silk canvas. The fabric is often stretched and primed to prepare for painting.

• Colors: Traditional Thangka artists use natural mineral pigments, ground from stones, gems, and plants. These colors are mixed with water and sometimes glue to create vibrant hues that last for centuries.

• Gold Leaf: Gold leaf is often applied to enhance the richness of the painting and to highlight divine figures or celestial realms, signifying their importance.

1. Preparation of the Canvas: The canvas is first prepared by stretching it over a wooden frame and applying a coat of chalk and glue. This preparation ensures that the paint adheres to the fabric and allows for a smooth, detailed surface.

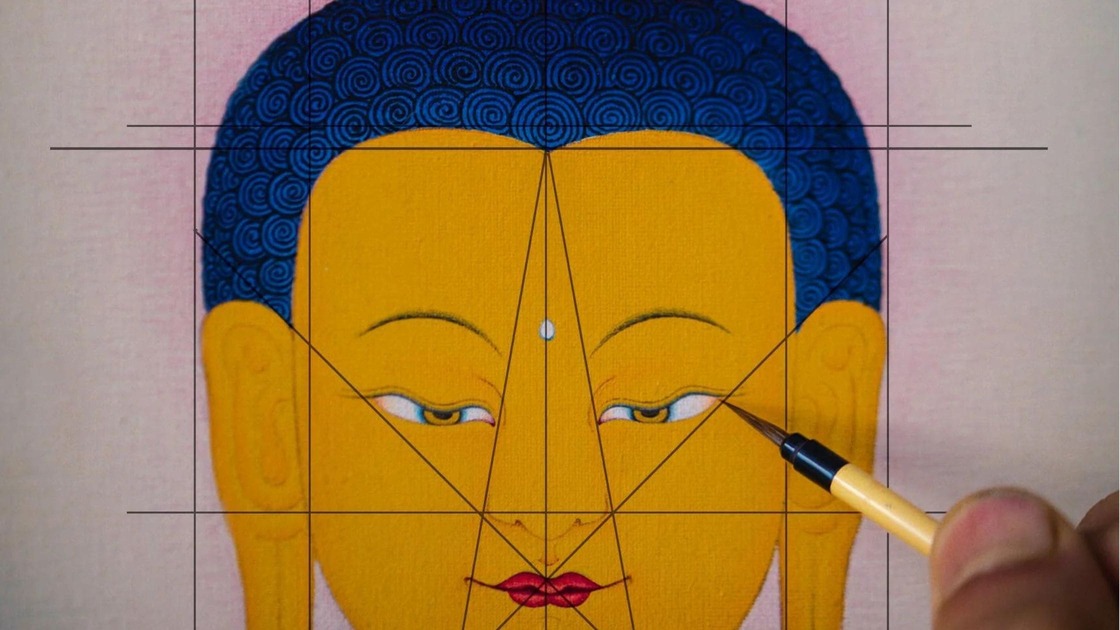

2. Sketching: The artist begins by lightly sketching the image using charcoal. The central figure is typically the most important aspect of the composition, surrounded by other figures or symbolic motifs.

3. Drawing the Outline: Once the initial sketch is complete, the artist uses a fine brush to outline the figures with black ink. The lines are drawn with great precision to reflect the strict guidelines of Tibetan iconography.

4. Filling in the Colors: The artist then begins filling in the colors, starting with the background and working towards the main figures. Each color has a specific meaning—red symbolizes power, green symbolizes wisdom, and yellow represents abundance.

5. Detailing: Finally, intricate details are added to enhance the painting. This may include fine lines, shading, and the addition of gold leaf. The gold accents add a divine and sacred quality to the painting.

6. Framing and Finishing: Once the painting is complete, it is mounted onto a silk brocade frame. The Thangka is often bordered with rich silk cloth, creating a beautiful contrast with the central painting.

Every aspect of a Thangka painting holds symbolic significance. The deities, colors, positioning of figures, and even the borders carry meaning that contributes to the overall spiritual message of the work.

• Deities and Figures: Each deity in a Thangka represents a particular quality or aspect of enlightenment. For example, Avalokiteshvara is associated with compassion, Manjushri with wisdom, and Tara with protection.

• Color Symbolism: As mentioned earlier, colors have deep significance in Tibetan art. For instance:

• Red: Often symbolizes power, passion, and the transforming power of meditation.

• Blue: Represents the wisdom of the Buddha.

• Yellow: Signifies the Buddha’s teachings and spiritual awakening.

• Green: Symbolizes balance and healing.

• The Mandala: The mandala, often featured at the center of Thangka paintings, represents the universe. Its concentric circles are a visualization of the cosmos and a guide to achieving spiritual enlightenment.

While the traditional methods of Thangka painting have been passed down for centuries, the art form continues to thrive in modern Tibet, Nepal, and India. Thangka artists are often trained in monasteries or traditional art schools, where they learn the intricate techniques and the religious significance of each element.

Today, Thangka paintings are highly prized by collectors and art enthusiasts worldwide. Whether as spiritual tools, decorative objects, or historical artifacts, these paintings offer a unique window into the rich cultural and religious heritage of Tibet.

Tibetan Thangka paintings are a testament to the spiritual depth and artistic mastery of the Tibetan people. As both sacred objects and works of art, they offer insight into the heart of Tibetan culture and the Buddhist path to enlightenment. The intricate details, vibrant colors, and powerful symbolism